Our country is in turmoil. There is protesting in the streets and many parents aren’t sure how to discuss these events with their kids. A common issue I hear from parents is this: how do we inform our kids about the current events and racial injustice in an developmentally-appropriate way while still helping them learn how to be actively anti-racist?

I’ve invited fellow parenting blogger Jen Lumanlan to write on this topic today. She’s well-versed in child development research and works to help parents discuss racism with their kids.

Note: We see Black parents and are listening and learning. This particular resource is intended primarily for White parents who feel called to do more intentional anti-racist work in their own lives and in raising their children, and who want to make a start.

Many parents are seeing the protests happening on city streets in the U.S. right now, and are struggling to understand how to talk about this with their child, or to know what to do. As the White parent of a mixed-race but White-passing child, I have the privilege of being able to avoid discussing this with her if it feels too uncomfortable to me – a privilege that is denied Black parents, who must discuss racism with their children early to keep their children safe. If you know you want to start discussing issues related to race and racism with your child but don’t know where to start, here are some research-based ideas to help:

How to get the conversation started

The best place to start a conversation on this topic is with your child’s questions. When they ask why helicopters are circling overhead, or they’re seeing boarded-up storefronts, answer their question clearly and succinctly: “People are protesting because a few days ago, a Black man called George Floyd bought something at a store and the person who worked at the store thought he used fake money. The worker called the police, and one of the police officers pulled George out of his car and held him on the ground by putting their knee on his neck. George couldn’t breathe, and he died.”

Don’t assume that just because you’ve never mentioned race to your child, that they haven’t noticed it. They’ve noticed the messages our culture sends about who is beautiful, who is powerful, etc. and that White children are ‘clean’ and ‘kind.’ Not talking about race doesn’t send the message that we have moved beyond race; it tells your child that the topic is too scary for you to discuss.

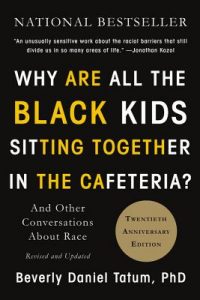

If you haven’t had conversations about race with your child before, you may find it easier to read books about race as an entry point. If your child’s main exposure to ideas related to race has been through preschool or school, it’s likely that they think that ‘Black people were mistreated, but Rosa Parks sat down on a bus and now there isn’t a problem anymore.’

I worked with Professor John Bickford to develop a list of children’s books that, when read as a set, cover the main ideas that the Southern Poverty Law Center says we need to teach young children about slavery and the Civil Rights Movement [download the list for free at yourparentingmojo.com/race].

Use developmentally appropriate language

This means using language and ideas that the child is ready to understand (while recognizing that parents of non-dominant cultures – a term I use to acknowledge that structural racism is as much about power as skin color, and to avoid centering whiteness above all other skin colors – do not have the luxury of waiting to tell their child about these events). If the child knows about death, they’re old enough to know that George Floyd and Dr. Martin Luther King died. If they’re old enough to know that guns and bullets kill, they’re old enough to know that Dr. Martin Luther King was shot and murdered. This conversation may still be uncomfortable for you, but if your child understands these concepts, they’re old enough for the conversation.

If your child is highly stressed by current events related to COVID-19, you may choose to hold off on the detailed descriptions for right now. But again, do acknowledge the privilege that allows you to do this – and make a plan to have a direct conversation about it as soon as possible.

Help your child to understand that violence is an expression of deep-seated emotions

It may feel strange to tell your child that you support people who are engaging in destructive behavior when it seems like we spend half our lives asking our child to stop destroying things around the house and hitting their sibling. It can be helpful to first understand for yourself why people are so angry that they feel that looting stores and setting fire to property is their best way to express their feelings.

Then you can explain it to your child: Black people have been told for a long time that their lives aren’t worth as much as White people’s lives. They’ve been trying to tell the rest of us for a long time that this isn’t fair, and not enough of us have listened. White people still kill Black people, even today, and right now some Black people (and some White people as well) feel like the best way they have to get our attention is to protest peacefully, while others break into stores and take things. The real problem isn’t that people are breaking into stores, but that Black people rightly feel that they aren’t treated fairly.

Take steps to engage in anti-racist work yourself

There is no such thing as being ‘neutral’ in this work. Either you’re actively working to dismantle systems of structural racism, or you’re supporting these systems. The first big step is to acknowledge that you have privilege. If you identify as White, even if you grew up (or are still) poor, you have privilege.

There’s a great list of activities you can do to start working for racial justice here. Involve your children in this work. When you join a reparations group, have them help you figure out to whom you should donate. Learn – together! – about the Native American tribe on whose ancestral land you live (I live on the land of the Chochenyo Ohlone, and I pay the Shuumi Land Tax). Support people of non-dominant cultures who are running for office. And vote for them.

Teach – and model – standing up against racially biased words and actions

When someone makes a racist joke, make a point to say that it isn’t funny. If your in-laws make racially biased comments in front of your children, make a plan with your spouse to approach them in a friendly, non-threatening way, and ask them to not make these comments in front of your child. You may not be able to change your in-laws’ minds, but you can control the ideas that are discussed in front of your child. Make a plan with your spouse for what you will do if future comments occur, and stick to your plans.

Talk with your child about what they should do if they see treatment of others that is unfair (e.g. racially biased comments at school, or rules that are applied differently to different people). If it is safe to do so (e.g. if there are other allies around who will back up your child), the child should speak up on the spot. If they cannot identify other allies, they can speak to another teacher, to the Principal, or to you after school. If they are in a public environment, it may be safer to be allies to others, by doing things like recording actions that they know to be wrong.

Systemic racism has been in place for many generations and it may take many more to completely erase it. It’s possible that we will never be able to fully achieve this goal. But if we don’t try; if we don’t start, we know it will never happen.

Try.

Start.

Today.

To download a free infographic of 10 steps you can take to raise an anti-racist child, and find a series of podcast episodes and blog posts to help you understand issues related to race and privilege, please visit yourparentingmojo.com/race

Jen Lumanlan holds an M.S. in Psychology (Child Development) and an M.Ed., and hosts the Your Parenting Mojo podcast which is a reference guide for parents of toddlers and preschoolers based on scientific researchers and the principles of respectful parenting. In each issue, she examines a topic related to parenting and child development from all sides to help parents understand how to make decisions about raising their children. She lives in California with her husband and daughter.

Related Resources:

Leave a Reply